|

|

|

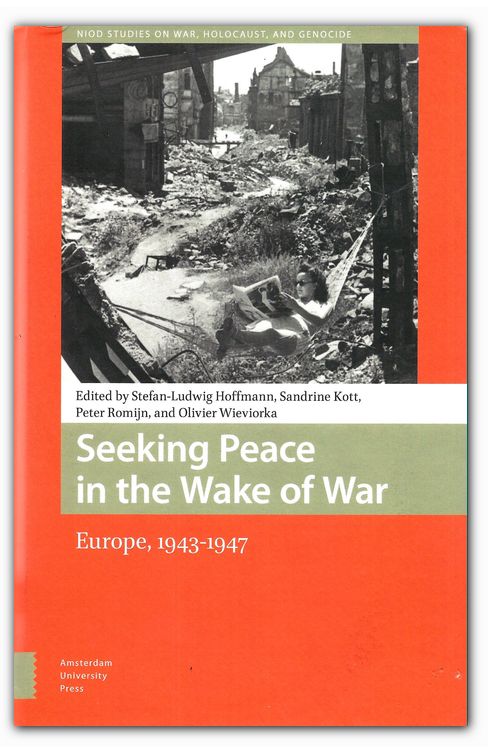

When

World War II ended, Europe was in ruins. Yet politically and socially,

the years between 1943 and 1947 were a time of dramatic

reconfigurations that proved to be foundational for the making of

today&;s Europe. This volume homes in on the crucial period

from

the beginning of the end of Nazi rule to the advent of the Cold War. It

demonstrates how the everyday experiences of Europeans during these

five years shaped the transition of their societies from war to peace.

The essays explore these reconfigurations on different scales and

levels with the purpose of enhancing our understanding of how wars end. Artikel: Seeking Peace in the Wake of War: Europe, 1943-1947 Herausgeber: Amsterdam University Press; 1. Edition (17. November 2015), (15. Juni 2016) Sprache: Englisch Gebundene Ausgabe: 360 Seiten ISBN-10: 9089643788 ISBN-13: 978-9089643780 Abmessungen: 15.24 x 2.54 x 22.86 cm Artikelgewicht: 680 g Preiß: 13,95 € Price: 130,18 $ Edition PDF: ISBN:9789048515257 |

|

Eröffentlicht von Amsterdam University Press 2015 Aus dem Buch Seeking Peace in the Wake of War: Europe, 1943-1947 Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann |

||

| Seeking Peace in the Wake of War: Europe, 1943-1947 | ||

| |

||

|

I

Returning to New York in the spring of 1950 after travelling for several months in post-war Germany, Hannah Arendt described with inimitable incisiveness the curious contrast between the horrendous destruction of German cities and the apparent indifference of their inhabitants. This juxtaposition, she conceded, could be found elsewhere in Europe as well: But nowhere is this nightmare of destruction and horror less felt and less talked about than in Germany itself. A lack of response is evident eve- rywhere, and it is difficult to say whether this signifies a half-conscious refusal to yield to grief or a genuine inability to feel. […] This general lack of emotion, at any rate this apparent heartlessness, sometimes covered over with cheap sentimentality, is only the most conspicuous outward symptom of a deep-rooted, stubborn, and at times vicious refusal to face and come to terms with what really happened.1 There are, in contrast, only a few paragraphs in The Origins of Totalitari- anism that directly address the question of how Hitler‘s Germans emerged from this experiential world at the moment of total defeat. When the terror ended, Arendt argued, so did the belief in those dogmas for which members of the Nazi party had been prepared to sacrifice their lives just a short time earlier. She attested to the suddenness of this turnabout, which many contemporary observers (and later historians) found so implausible and morally vexing. It was only on her trip through post-war Germany that Arendt believed she also recognized the ‘aftermath of Nazi rule’, both the rupture and the continuity. Arendt did not regard the Germans she encountered in 1949 as Nazis. Nevertheless, she believed that as a result of the experiential world of the Third Reich they lacked any form of human empathy, whether for their own dead, the suffering of refugees, the sight of the demolished cities or the fate of the murdered Jews. More than sixty years after the end of the war, the question Arendt posed about the emotional turmoil that accompanied the transition from total war to cold peace remains at the centre of historical-political debates of Post-Cold War Germany. In his essay ‘Air War and Literature’, W.G. Sebald reformulated this question into the widely discussed claim that the scope of destruction in German cities had left scarcely ‘a trace of pain’ in the German collective memory. According to Sebald, after 1945 the Germans had lived as if the horror of the war had passed over them like a nightmare, mourning neither the dead nor the destruction of their cities. They not only remained silent after the war about their involvement in the crimes of the Nazi regime, Sebald argued, but also never really put into words the extreme collective experiences of the final year of the war.4 Sebald‘s thesis provided the unintentional impetus for a wave of recol- lection in the German media that – after ‘coming to terms’ with the crimes committed in Europe by the Wehrmacht and the Nazi Sondereinheiten Nevertheless, the 1940s – the period between the Wannsee Conference Between these two extremes lies the watershed moment of the end of the war, understood here as a f ive-year intermediate period that began in 1943 with the looming German defeat in Eastern Europe and that came to a close only in 1947 with the inception of the Cold War. The few years between the catastrophic defeat and the beginning of occupation rule constituted a dramatic phase of upheaval, not only for German society. While the political reordering of the world and of Germany in 1945 has been well researched, less attention has been paid to questions about perceptions of this epochal upheaval: How were war, genocide, destruction and occupation inscribed in the language of contemporaries? How did the victors and the vanquished emerge from the existential enmity of war? Where are the emotional traces of violence evident? In other words, contemporary historians have only begun to address the question raised by Hannah Arendt and W.G. Sebald about the subjective perceptions of the participants during this epochal rupture. Even contemporary witnesses, when questioned today about this experiential world, speak of it as a foreign and unreal no-man’s land. The following reflections thus begin with the hypothesis that a history of this watershed moment of the 1940s should begin with the analysis of those private texts – especially diaries – in which contemporaries recorded their perceptions of events as they were unfolding. At the moment of an epochal rupture, previous expectations collapse and new realities emerge that follow different rules of what can be expressed. ‘History itself always occurs only in the medium of the participants’ perceptions’, as Reinhart Koselleck has noted. The notions of the actors about what they do and about what they should not do are the elements from which, perspectivally fragmented, histories coalesce. Notions and will-formation, desires, linguistically and prelin- guistically generated, perceiving something to be true and holding it to be true, these are all incorporated into the situation, from which events crystallize. What the different agents regard as real about a history as it emerges and thus carry out in actu constitutes pluralistically the coming history.7 This also means that the catastrophic experience of rupture and upheaval in the 1940s cannot be understood solely from a single perspective – and this, drawing upon Koselleck, is my second hypothesis. The fundamen- tally different perspectives of the vanquished, the occupiers, and the liberated constitute the ruptured experience of genocidal war, occupation II

It was in diaries that the inhabitants of German cities copiously detailed the horrors of the war as well as their own expectations and experiences connected to the defeat. At no other point in the history of the twentieth century does the practice of keeping a diary appear to have been so wide- spread as during the Second World War.9 German diaries frequently began around the turn of 1945 and ended already a year or two later. They were written explicitly to record the scope of the external and internal destruc- tion under National Socialism as well as the new experiences following Germany’s total defeat, in particular those with the victors. Only recently have historians discovered diaries as a source of subjective perceptions of war and genocide, part of a general trend that Annette Wie- viorka has called ‘the era of the witness’.10 Although a few diaries published in the immediate post-war period did become, so to speak, representative of the experience of the world war, historians today have access not only to hundreds of diaries kept by Hitler‘s Germans, but also to those written by persecuted and murdered Jews as well by members of all the nations that participated in the war, including the Soviet Union.11 These texts have yet to be analysed as the basis of a history that integrates the different perspectives on the epochal rupture of the 1940s. The diaries certainly do not contain any kind of authentic (or resistant) subjectivity beyond the hegemonic political discourses of the era. On the contrary, the diaristic monologue was a standard practice of the politiciza- tion of the self in totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century, as Jochen Hellbeck and Irina Paperno have recently argued in their studies on diaries under Stalinism.12 Precisely this makes diaries interesting for the analysis of contemporary perceptions of the self and others. It is also something that diaries share with autobiographical and literary texts, for which they often serve as a starting point and as material. Retrospectively composed autobiographies, biographical interviews and novels do provide information primarily about later political ‘sub- jectivizations’ (in the dual sense of self-formation and subordination). In these texts, the initial inscriptions in a diary, the emergence of new ways of seeing the past and the future are followed by a ‘re-writing’ of these earlier experiences and expectations. All too often this distinction has been levelled, for instance, in Walter Kempowski‘s Echolot, but also in more recent historical studies, for instance, Catherine Merridale‘s examination of Soviet war experiences, in which autobiographical texts from different eras are mixed together without always identifying the temporal distinctions.13 Diaries can certainly also become the objects of later ‘re-writings’. One example of this was the debate in the German media about the new edition of the diary Eine Frau in Berlin (A Woman in Berlin) by Anonymous (Geneva, 1959)14 in the Die Andere Bibliothek series by Hans Magnus Enzensberger several years ago, during which the identity of the author was definitively resolved, but not the question of when the published version was actually composed. The German Literature Archive in Marbach recently published Erich Kästner‘s diary notes, the language of which deviates from his pub- lished diary Notabene 45. Ein Tagebuch (Zurich, 1961). Yet another example is the well-known diary by Karla Höcker Beschreibung eines Jahres. Berliner Notizen 1945, originally published in 1966. There are four different versions of this diary: first, the handwritten notes in a pocket calendar from 1945 recording the events; a typewritten transcription in late 1947; and finally the published version of 1966 and the second edition of 1984. The 1947, 1966 and 1984 versions deviate from the original through respective addi- tions and omissions. These rewritings are noteworthy precisely because Höcker, a musician and writer, was not a Nazi and had nothing to hide in her biography. It was the ambivalent political expectations about the end of the war in 1945, contained in Höcker‘s original diary, that were ‘corrected’ in the subsequent versions. For example, the following entry from April 22, written in expectation of the Red Army’s conquest of Berlin, was omitted from the published editions: And yet one lives somewhere deep inside, and the sweetness of life, the not-yet-savored, the love of everything that makes life f irst worth living at all is more intense than ever. [...] A heavy strike apparently quite near forces us all into the basement. Strange atmosphere, a mixture of ski hut, youth hostel, revolutionary basement, and opera romanticism. Many unfamiliar people – only in this situation does one realize how unfamiliar they are – attempt to sleep, while outside a new epoch begins. The end, the beginning of Europe? The decline of the Occident? No one knows – and I experience the desire to sleep while this occurs. After the fall of the city, Höcker and her friend Gustav Gründgens had to clear away the street barricades earlier erected by forced labourers; her entry on 5 May, which described this, was already omitted from the 1947 transcription: The Commandant’s Office on Kaiserdamm 88: a line of people, a Russian soldier smiling good-naturedly, a young officer with a hard and arrogant expression. Everything still seems to be very much in the making. One is given hardly any information. Of the many radio listeners in our city district, barely 30 have turned theirs in. The image of the street continues to be colourful and strange: A destroyed military glider, automobile parts, and a plundered tank lie on the Kaiserdamm; there are still swastika flags everywhere; the [swastika] cross has been removed from most of them, but the circle where it used to be is still visible. [...] It is remarkable that all of these deeply depressing external circumstances make us neither sad nor ill-humoured, nor put us ‘in a bad mood’. Only the passing victorious troops – with red flags and [spring] green – followed by long columns of German prisoners casts a shadow on our souls. Then suddenly the crass- ness of the situation becomes completely apparent: We, the musicians, artists, citizens, the women and children of the German people, clear away as a pointless traffic obstacle, the barricades on which our men were supposed to f ight the enemy, while these men, after six years of war, head out as prisoners – into the unforeseeable. And Asia triumphs!15 It was the images and emotions intended to capture the incursion of events, the ‘enormous fissure that has torn through our lives’, as Höcker wrote on 12 July, that were eliminated from the 1947 version of the diary. The urban destruction, the violence of the Red Army, the humiliation in everyday life for the vanquished (Höcker, for example, had to turn over her house to the British authorities), but also the uncertain future at the end of the war, all of this was either narrated in a linguistically defused form deemed more appropriate for the times or completely omitted in subsequent versions.16 Like no other source, diaries allow for the precise reconstruction of how the political expectations of Hitler‘s Germans changed in the f inal two years of the war (which also conditioned their perceptions of the foreign occupation) and in the first months after the war. It is the expectations, as formulated in these private chronicles, that explain the apparent contradiction of why the Nazi regime, despite its imminent catastrophic defeat, was able to secure the allegiance of many Germans until the bitter end, and at the same time why after the end of the war the transition to a peaceful order could be achieved so astonishingly quickly. As indicated by the diaries as well as other sources (for example, reports on the popular mood collected by the Gestapo or the interrogations of German prisoners of war), it was the expectation of violent reprisals by ‘the Jews’ (usually associated with British and American aerial warfare) and the ‘Bolshevists’ (the advancing Red Army) that caused many Germans to ‘hang on’ in the Nazi war. In the last years of the war, the propaganda of the Nazi regime as well as that of the Allies sought to level political distinctions between Germans and Nazis. Beginning in 1942, the Nazi regime indirectly confirmed rumours about the ‘Final Solution’ and the genocidal war in Eastern Europe in the press, seeking thereby to turn Germans into knowing accomplices of the genocide. In this way the ‘Final Solution’ became an eerie, open secret and a catalyst of German war society, irrespective of who had actually participated in the concrete crimes. Thus the ostensible Volksgemeinschaft became a kind of Schuldgemeinschaft or ‘community of guilt’ that feared the end of the war no less than its continuation.17 ‘The overall picture is that of collective entanglement’, as Rafael Zagovec notes, ‘which was initially introduced with a light hand, then solidified through the alleged war successes, and, when it could no longer be ignored that this regime had long abrogated all ethical norms, became a community of guilt, in which the fear of one’s own terror apparatus and of revenge by the enemy were tied in an indissoluble bond’.18 This ‘community of guilt’ The anticipation of catastrophic defeat and subjugation marked the perception of the diarists even in their dreams. These dreams, in turn, provide insight into the experiences of the witnesses in eventum.20 For example, nine-year-old pupil Sabine K. wrote on 2 May 1945: On Wednesday night I slept very poorly. I dreamed that a Russian came to us in the basement and asked for water. Since no one else had the courage, I stood up; I had to go along a corridor somehow, then suddenly a yellow light shone on a downright Chinese physiognomy. With the most revolting sound of his lips smacking, he tore my coat off and touched me. Then I was awakened by the sound of an automobile outside our house. Now I was also terribly cold, I began to shake horribly. Mother was also awake. I stuttered softly, ‘You know, I think they are here!’ The next day the family had their first encounter with the victors, which was quite different than Sabine K. had expected: As I stand in my room in front of the mirror on the balcony window, a brown figure rides by on a bicycle and smiles up in a friendly way. I think I’m not seeing right, but it was really the first Russian. Cars soon appeared here and there; we went to the house next door and stood with J., Frau M., and Fräulein T. in front of the door. Then a very nice young guy came by again on a bicycle; a woman from number 50 said something to him, quickly brought out some schnapps, and had him show her the situation In other diaries as well, we find this juxtaposition of fears about revenge by the victors (often enough justified), relief about the peace, and simultane- ously profound dismay about the defeat. Another Berlin schoolgirl noted on 9 May, as news of the unconditional surrender spread: ‘Germany has lost the war! Everything has been in vain! Our soldiers have died in vain, fought in vain! All of the efforts have not helped at all! Who would have thought it? [...] We are nevertheless pleased that peace has now returned!’22 The first contact with the victors in the fallen cities left no doubts that the Red Army intended to exact revenge for German crimes in the Soviet Union. For many Germans the Second World War ended with Soviet soldiers forcibly entering their private quarters, not only to engage in violence or to plunder, but also to confront the defeated enemy. Virtually every diary from the Soviet occupation zone includes scenes in which soldiers and officers of the Red Army seek out conversation with Germans and show them photographs of murdered relatives. In several cases these frequently drunken encounters end in scenes of fraternization, in others in mock executions, preceded by In June 1945, German writer Hermann Kasack described retrospectively in his diary such an encounter with a Soviet officer in his villa in Potsdam: Then, however, he began to tell with growing agitation about his sister, who, as we had to have Fräulein Kauffeldt translate for us, had been tortured and abused at age seventeen by a German soldier; the soldier, as he put it, had had ‘red hair and eyes like an ox’. We sat uneasily as the Georgian officer cried out full of rage that when he thought about it he would like to break everyone’s neck. ‘But’, he added after a pause, ‘you good, you good’. He also pointed out that he had maintained his form and composure, as we had to admit. Time and again he became enraged about the fate of his unfortunate sister, and again, as so often in these days and weeks and actually in all the Nazi years, we felt ashamed to be German. After a time, which seemed endless to us but was hardly more than an hour and a half, he departed telling us he would be back the next day. [...] How disgraceful, how dishonourable to have to be German.24 Even for those who had waited for the end of Nazi rule and regarded the Red Army as their liberator, the occupation seemed like a bad dream. Martha Mierendorf, whose Jewish husband had been murdered in Auschwitz – something she already suspected in the spring of 1945 but did not know for certain – noted on 27 April: ‘I must endure whatever happens to me and regard it as payment for the debt incurred by Hitler and his gang.’ On 5 May, however, she also wrote: ‘Every morning when I awake, it is only with great effort that I can get used to the fact that a strange world awaits outside, that everywhere my steps take me there are Russians and more Russians. That everything the victors want has to occur. Only now does everyone feel what a lost war means.’ On 1 September, after four months of occupation rule and a nightmarish dream about a fit of rage against the Russians that ended with a nervous breakdown the following morning, she wrote: ‘The destroyed city gnaws incessantly on my nerves and disturbs my mind, without me directly noticing it. Every step through the ruins hammers chaos, violence, and despair into my brain. It is unsettling to observe peoples’ efforts to save themselves and the city.’25 The transition from war society to the occupation period occurred with a violent abruptness that contemporaries already comprehended as an epochal break. ‘Newspapers that are only a few weeks old appear strangely unreal – so that it makes one shudder!’ actress Eva Richter-Fritzsche wrote in her diary in Berlin on 4 May 1945.26 Ernst Jünger noted in Kirchhorst north-east of Hannover on 15 April 1945: ‘A sense of unreality still pre- dominates. It is the astonishment of people who stand upright after a heavy wheel has run through them and over them.’27 People were stunned not by the violence tied to the upheaval (which, on the contrary, was described especially in women’s diaries with conscious laconism28) but rather by the catastrophic scope of defeat in a war that Nazi Germany had conducted in such manner that the vanquished could expect no peace. In retrospectively written autobiographies (or subsequently rewritten diaries), the catastrophic nationalism and the racism towards the Soviet occupiers (and previously towards the Eastern European slave labourers) were often eliminated. Connected to this, most of them also omitted the recognition contained in diaries of 1944 and 1945 that given their own brutal occupation and genocidal war in Eastern Europe Germans could expect no leniency from the victors, as well as the relief that an unconstrained interaction with the occupiers could soon begin. This was one of the reasons why, contrary to Allied expectations, Germans offered no serious resistance to foreign occupation after the war. In contrast to France in 1871 or Germany in 1918, the ‘culture of defeat’ of the vanquished after 1945 did not aim at revenge.29 As Dolf Sternberger III

The occupiers, the vanquished and the

liberated perceive events differ- ently.

At the same time, however, their often asymmetrical perceptions are so

intimately related that they have

to be analysed in their historical entanglement.

This is particularly true for total wars and semi-colonial occupation

regimes, which arrived in

Europe with Nazi genocidal policies in

the 1940s. As acting observers, the participants and their perceptions are part of

the events. These perceptions

co-determine how a conflictual

interaction

takes place and the significance it is retrospectively ascribed. This insight,

long recognized as a matter

of course in postcolonial studies, is

by no means widely accepted in contemporary history. The reasons for this are not

merely ideological (for

instance, the adherence to national- historical master narratives that always only

accentuate one’s own national perspective) even

if

in

a

critical

manner.

Government

sources,

organized

in

national archives, also constitute a

problem for this kind of transnational history.

The plans and decrees of occupation bureaucracies, the opinion surveys and

reports on the popular mood

commissioned by them, the

tribunals

and

re-education

campaigns

all

provide

only

limited

information

about the

contingent interactions between occupier and occupied and their mutual

perceptions. How does our perspective on Germany’s watershed years

between

1943

and

1947

change

when the perceptions of the Allies – asThe private notes of the vanquished were often written exclusively for absent family members and were published only in isolated cases (and with greater temporal distance). The situation is completely different for the diaries, letters and travel reports of the Allies. In 1945 and 1946 the Allied media were f illed with eyewitness reports of post-war Germany, although this interest did wane quickly. George Orwell, Stephen Spender, Edith Stein, Dorothy Thompson, Norman Cousins, Melvin Lasky, Alfred Döblin, Max Frisch, Vassily Grossman, and Il’ja Ėrenburg – there was hardly a well-known intellectual of the era who did not travel to Germany after the war to write about the vanquished enemy, either as an occupier or as an observer. However, the overwhelming impression of war and desolation also led thousands of members of the occupation armies and administrations to record and to publish their own perceptions, whereby internal and external censorship also resulted in significant rewriting of their private notes. This was particularly true for the Soviet side, where the discrepancy with off icial propaganda was especially evident, but was initially the case for the West as well. The Allies’ moral condemnation of the Germans at the end of the war often contrasted sharply with the concrete experiences with the vanquished recorded in their private notes. The Allies came to Germany not as liberators, but as conquerors. The German defeat was unconditional not only militarily, but also morally and politically. The victorious powers agreed that the supreme goal was to defeat and punish Germany for the crimes committed during the war. In 1945, Germany and Japan were regarded as enemies of humanity and ceased to be sovereign subjects of international law. Before soldiers of the Allied occupation entered the country, they were instructed in meetings and in informational brochures to make no distinction between Germans and Nazis.31 The Allies also expected that there would be bitter partisan The fact that the German civilian population had waited for the end of both Nazi rule and the war and readily accepted Allied occupation was thus one of the unexpected and confusing experiences for occupiers on the ground, who noted this incredulously and often with rage in their diaries and letters. Konrad Wolf, for example, a lieutenant in the Red Army and son of émigré German writer Friedrich Wolf, wrote (in Russian) in his diary outside of Berlin on 19 March: I must say that the few inhabitants who have remained in our section seem terribly frightened by German propaganda; for this reason they say what we want to hear only to please the Russians. They whine that Hitler and Germany have come to an end. One encounters much cajolery; at times it is simply awful. [...] All more or less major cities have been severely damaged, in part through bitter fighting, in part also through the hatred of our soldiers. [...] Many of my acquaintances here, indeed even friends, probably think that I see this all and feel sorry for the German cities, the population, etc. I say quite openly, no, never will I regret this, for I have seen what they have done in Russia.32 Another Red Army soldier wrote in a letter home from Berlin on 27 May: When I now cross the street, the German rabble (petura) bows down to the ground (just as it does to all the soldiers and officers of our unit). I believe this is not because they love and respect us. It is because they Again and again the faces of submissive Germans are described in the diaries as ‘beastly’ (zverskij).34 At this point in time there was hardly any difference between the language of the private diaries and official Soviet war propaganda.35 The Germans had left a gruesome trail of violence in Eastern Europe, especially in their labour and extermination camps, the significance of which is difficult to overestimate for the perception of advancing Red Army forces. For this reason the ruins of demolished German cities made no great impression on them. One soldier, for instance, wrote laconically in a letter home on 9 May 1945: ‘Berlin has been destroyed down to its foundation walls, like our Michajlov.’36 Four days later, a major who had been a philosophy professor in Voronezh before the war wrote to a former colleague: ‘I looked at the ruins in Berlin and said to myself, that is the bill for Stalingrad, for Voronezh, for thousands of burned down cities of ours.’37 Irrespective of the desire for revenge, Soviet eyewitness accounts also expressed horror at the violence against German civilians. One officer recorded his impressions of such a transgression: Burning German cities. Traces of short-lived battles on the roads, groups of captured Germans (they surrendered in large groups, fearing they’d be shot if they did so individually), corpses of men, women, and children in apartments, lines of carts with refugees, scenes of mass [illegible], raped women [illegible, crossed out by the author] [...] abandoned villages, hundred and thousands of abandoned bicycles on the road, an enormous mass of cattle, all of them bellowing (no one was there to feed the cows or give them water) – all these were “battle scenes” of the offensive by an army of avengers, scenes of the devastation of Germany which compelled The writer and popular war reporter Vassily Grossman, who had written the first eyewitness account of the remains of the extermination camps in Treblinka and Majdanek in 1944 and had learned that year that his mother, like all the Jewish inhabitants in the Ukrainian city of Berdychiv, had been murdered by German Einsatzgruppen in 1941, noted in his diary in Schwerin in April 1945: Horrifying things are happening to German women. An educated Ger- man whose wife has received “new visitors” – Red Army soldiers – is explaining with expressive gestures and broken Russian words that she has already been raped by ten men today. The lady is present. Woman’s screams are heard from open windows. A Jewish officer, whose family was killed by Germans, is billeted in the apartment of the Gestapo man who has escaped. The woman and the girls [left behind] are safe while he is here. When he leaves, they all cry and plead with him to stay. In the language of Grossman‘s diary we can already recognize the anti- totalitarian author of Life and Fate who knew the meaning of Stalinist rule: ‘The leaden sky and awful, cold rain for three days. An iron spring after the iron years of war. A severe peace is coming after the severe war: camps are being built everywhere, wire stretched, towers erected for the guards and [German] prisoners urged on by their escorts.’ And then after the conquest of Berlin, he wrote: Prisoners – policemen, officials, old men and next to them schoolboys, almost children. Many [of the prisoners] are walking with their wives, beautiful young women. Some of the women are laughing, trying to cheer up their husbands. A young soldier with two children, a boy and a girl. Another soldier falls down and can’t get up again, he is crying. Civilians are giving prisoners water and shovel bread into their hands. A dead old woman is half sitting on a mattress by a front door, leaning her head against the wall. There’s an expression of calm and sorrow on her face, Such descriptions of the German defeat did not appear in the official press of the victorious powers in the spring of 1945, even in the West. On the contrary, it was the photographs and reports of the liberated concentration camps in Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald in the American and British media in April 1945 that first really ignited the moral condemnation of the Germans at the end of the war.40 Many members of the British and American occupation administration came to Germany with these images in their heads. ‘I was delighted to find myself wholeheartedly anti-German as soon as we crossed the border’, a British lieutenant wrote in his pocket calendar on the way to Berlin on 27 May. ‘What infuriated me was to see them so well dressed and complacent.’41 Nevertheless, the Western Allies’ initial encounters with the German civilian population differed from those of the Soviets. Arriving in Berlin, the aforementioned British officer, who would be appointed commander of the Tiergarten district of Berlin, wrote on 1 July: ‘We were all very impressed by the fact that the Germans were very [crossed out by the author] glad to see us.’ When British troops officially entered Berlin a few days later, they were celebrated by the population and greeted with flowers, ‘because it means for them the real end of the war and that the presence of the Russians had seemed too much like War.’42 In a letter (on captured handmade stationary It was not only in Berlin that Germans greeted the British and Americans as liberators following the military defeat, a reversal that the Soviet side observed with mistrust. Leonard Mosley, who accompanied the British occupation army as a war reporter, described similar scenes in the Ruhr: One could understand the people being relieved at our coming; one could understand the old warriors from the trade unions of pre-Hitler days, the staunch anti-Nazis who had escaped the concentration camps, coming out to welcome us. But the noisy, demonstrative greeting of so many, the obvious happiness of all who saw us, was a phenomenon that I f ind hard to explain; yet there it was. The conquering army rode into the Ruhr and thus sealed the doom of Nazi Germany; and the German workers, for whom this was defeat, cheered our coming and celebrated it in practically every city we visited.44 George Orwell reported with no less astonishment, although more scepti- cism, from south-western Germany in May 1945: ‘At present the attitude of the people in the occupied territory is friendly and even embarrassingly friendly.’45 Edgar Morin also began his travel report L’an zéro de l’Allemagne (published in Paris in 1946) by noting his surprise at the friendly submis- siveness of the Germans he encountered.46 The expectation of a civil war against the occupation and the experience of acquiescence by the German civilian population in defeat – in the case of the British and Americans even being celebrated as ‘liberators’ – was a contradiction that the Allies could understand only as political hypocrisy.47 There is hardly a diary or travel report that does not express indignation about the fact that after the defeat the Germans suddenly no longer wanted to be Nazis and that they concealed or withheld their ‘true’ feelings, which could only have been hatred of the occupiers. For this reason, the initial friendly interactions with the German civilian population immediately after the war appeared politically suspicious. The prohibition on fraternization issued by the Allies to punish the Germans and to protect their own soldiers in the case of a guerrilla war soon proved to be pointless, as the diaries richly illustrate. For German and Soviet diarists as well, the interactions between vanquished and occupier – not only the open liaisons between Allied soldiers and German women – were the most significant impressions of the initial post-war months. This all too unconstrained interaction with the defeated enemy became the prevail- ing issue of the occupation, to which the Western democracies responded differently from the Soviet Union. Even more than the violence at the end of the war, it was the lawlessness and terror through which the Stalinist regime sought to prevent this contact between occupier and vanquished in everyday life that cost the Soviet Union any moral credibility it had earned in the war against Nazi Germany. Whereas the British and the Americans came to Germany with a strict prohibition on fraternization that they gradually loosened the closer the vanquished and the occupiers became in everyday life, the Soviet troops were completely separated from the German civilian population (and the Western Allies) beginning in 1946 and all private contact with Germans was forbidden. Many Soviet officers and soldiers subsequently deserted to the West, often with their German lovers.48 In the diary of young Soviet lieutenant Vladimir Gelfand – the most important subject of which was his relationships with German women (and the formal calls he paid to their families) – desperation about the restrictions imposed by the victors was already evident in August 1945, when the first measures regarding the barracking of Soviet soldiers were introduced: Now it is time to rest a bit, to see what one has never seen before – the world abroad – and to become acquainted with that which one knew so little about and which one had no clear idea about – the life, the mores and customs abroad – and f inally also to go into the city, to see people, to talk to them, and to drive around, to enjoy a tiny bit of happiness (if this should exist in Germany). We have been forbidden to speak to the Germans, to spend the night at their residences, to purchase anything from them. Now the final things have been forbidden – to visit a German city, to go through the streets, to look at the ruins. Not only for soldiers, for officers as well. But this can’t be true! We are humans, we cannot sit in a cage, all the more so when our duties do not end at the barracks gate and we’ve already had it up to here with the conditions and life in the barracks, darn it all. [...] What do I want? Freedom! The freedom to live, to think, to work, and to enjoy life. Now all this has been taken from me. I have been denied access to Berlin.49 Over the next two years Gelfand, who was stationed outside Berlin, was able repeatedly, albeit with increasing difficulty, to arrange assignments in the city. ‘Here there is more freedom’, he noted on 14 January 1946, after such a visit. On the streets ‘one frequently sees Red Army soldiers walking arm in arm with German women or embracing them. There is no separate entrance for cinemas and theatres, and the German restaurants are always quite full with officers.’50 During subsequent visits, the last of which occurred in late 1946, Gelfand was troubled by the conspicuous contrast between the vanquished, who enjoyed ever more freedoms and abandoned their fearful respect of the occupiers, and the Soviet victors, whose freedoms were curtailed in every respect – an impression reinforced by visits to a homeland ravaged by war under Stalinist rule. The changes in the way ‘Russians’ were depicted in British and American diaries and travel reports on the basis of contacts on the ground in occupied post-war Central Europe is a significant issue that has received almost no attention to date. In the spring of 1945, the Allies still dismissed German reports of Red Army violence as Nazi horror propaganda. Beginning in the British and American diarists certainly also regarded the suffering of the German civilian population as just punishment for German crimes, not least those committed in extermination camps. This changed, however, over the course of 1945. At the beginning of December Isaac Deutscher, who had reported from Germany regularly for the British Observer since the end of the war, wrote: A few months ago criticism of inhuman and unreal conceptions of a Carthaginian peace were still regarded as some sort of heresy. Even mild and decent people seemed to breathe revenge. Now the pendulum has swung almost to sentimental sympathy for defeated Germany. ‘We must help Germany to get back on her feet’ has become a fashionable phrase.53 This sentimental sympathy can be found in many letters and diaries of Western observers, including those of returning émigrés. Peter de Men- delssohn wrote (in English) to Hilde Spiel in London on 18 November 1945 that, although he did not want to diminish what they had gone through together in England during the war, it was nothing in comparison to that which ordinary people had gone through in the completely demolished city of Nuremberg. ‘One wants to turn one’s face away and never look at it again. The last thing one feels like doing is passing sweeping judgements over old women and little pale children playing in indescribable ruins, children with one leg, one arm, blown-off hands, scarred faces etc.’54 For Western observers, life among the ruins of German cities paradoxi- cally became the symbol of the cultural catastrophe and the watershed experience at the end of the war. Stephen Spender, for instance, noted in his diary in October 1945 after a tour of the former Reichshauptstadt: Later, we made our way across the ruins of the city, to see those sights which are a very recent experience in our civilization, though they have characterized other civilizations in decay: ruins, not belonging to a past civilization, but the ruins of our own epoch, which make us suddenly feel that we are entering upon the nomadic stage when people walk across deserts of centuries, and when the environment which past generations have created for us disintegrates in our own lifetime. The Reichstag and the Chancellory are already sights for sightseers, as they might well be in another five hundred years. They are the scenes of a collapse so complete that it already has the remoteness of all f inal disasters which make a dramatic and ghostly impression whilst at the same time withdrawing their secrets and leaving everything to the imagination. The last days of Berlin are as much matters for speculation as the last days of an empire in some remote epoch: and one goes to the ruins with the same sense of wonder, the same straining of the imagination, as one goes to the Colosseum at Rome.55 There was hardly a diary or travel report that did not include detailed descriptions of the German landscape of ruins, which over the course of the year increasingly marked the public image of Germany in the West. These documents testified to the shock about the surreal everyday life in an occupied country. John Dos Passos, for example, wrote in his travel report in 1946: ‘The ruin of the city was so immense it took on the grandeur of a natural phenomenon like the Garden of the Gods or the Painted Desert.’56 After visiting a Berlin bar where German women danced with the victors, Dos Passos wavered between repulsion and pity. He identified the limits of empathy: As I lay in that jiggling berth in the military train out of Berlin, I was trying to define the feeling of nightmare I was carrying away with me. Berlin was not just one more beaten-up city. There, that point in a ruined people’s misery had been reached where the victims were degraded beneath the reach of human sympathy. After that point no amount of suffering affects the spectator who is out of it. […] Once war has broken the fabric of human society, a chain reaction seems to set in which keeps on after the f ighting has stopped.57 ‘Two wrongs don’t make a right.’ This final sentence of Dos Passos‘s travel report from occupied Germany soon defined the basic tenor of a critique of the Allies’ punitive treatment of the vanquished enemy, not only in private notes but in part also in the public opinion of Western democracies, which ultimately led to a liberalization of occupation policies. Swedish writer Stig Dagerman formulated an unusually harsh version of this critique in a travel report on the Western occupation zones in 1946: Our autumn picture of the family in the waterlogged cellar also contains a journalist who, carefully balancing on planks set across the water, in- terviews the family on their views of the newly reconstituted democracy in their country, asks if the family was better off under Hitler. The answer that the visitor receives has this result: stooping with rage, nausea and contempt, the journalist scrambles hastily backwards out of the stinking room, jumps into his hired English car or American jeep, and half an hour later over a drink or a good glass of real German beer in the bar of the Press hotel composes a report on the subject ‘Nazism is alive in Germany’. […] The journalist […] is an immoral person, a hypocrite. […] His lack of realism here consists in the fact that he regards the Germans as one solid block, irradiating Nazi chill, and not as a multitude of starving and freezing individuals.58 As a rule, however, criticism was directed at the lawlessness and violence of Soviet occupation, particularly after the beginning of the Cold War. It is no coincidence that the two most cited reports even today on Red Army violence at the end of the war initially appeared in English. Ruth Andreas-Friedrich diaries were published in New York in 1946 as Berlin Underground and then a The inception of West German democracy is thus marked not only by the geopolitical constellation of the Cold War, the imposed democratization,62 and the currency reform, which triggered the ‘economic miracle’ of the 1950s. Prior to these were the expectations of the final war years, the different private experiences in the encounters between Germans and Allies at and after the end of the war, and the moral narratives that arose from these transnationally intertwined relations. From these encounters between occupier and occupied an independent political dynamic emerged that could be controlled only with difficulty and that, as I have argued here, influenced the divided post-war order in a sustained manner.63 The way Germans dealt with their own guilty involvement with the Nazi regime drew its essential impulses between 1943 and 1947 from the historically contingent confrontation between Germans and Allies and their asymmetrical perceptions at the end of the war. For Soviet occupiers, who came from a country that had been demolished by Nazi Germany, the destruction of German cities was seen as a just form of reprisal, particularly given the fact that the Germans they encountered at the end of the war were invariably better nourished, better clothed, and possessed more material wealth than their own families had ever had. The hatred and hostility of the war continued on both sides in peace, irrespective of the propaganda of German-Soviet friendship introduced shortly there- after, which rarely corresponded to an everyday lived reality in the early years of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). ‘For people of a different generation, those who have not felt it themselves, it is impossible to imagine the entire extent of the hatred of Germans that accumulated during the war years’, one member of the Soviet occupation administration recalled in the early 1980s. ‘Even later, when this hatred of Germans slowly disappeared, when they became normal people for us, an invisible, insurmountable bar- rier remained between us.’64 For Soviet soldiers and officers, the encounter with Germans meant not only the hour of retribution, the moment when they could, in a reversal of German racism, become the masters of the master race. It also meant – as the diaries indicate – the recognition that peace would not bring them the freedom they had hoped for and that the life that awaited them at home also made them the losers of this war.65 Shock about the demolished German cities and the desolate, humiliating everyday life under foreign occupation was, in contrast, a privilege of Western observers and of a post-war humanitarianism that had experienced first-hand neither the immense scope of Nazi extermination nor the war brutally conducted by the two totalitarian regimes between the Volga and the Elbe. Paradoxically, for Western observers it was devastated and oc- cupied post-war Germany (and not, for instance, the desolate death zone left by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe) that became the symbol of a war that had destroyed the principles of civilization. The vanquished become the speechless, passive victims of this war – an attribute that Germans I feel sorry for them when I see how they starve, how they suffer (that is precisely what makes me so tired), but it is not my fault. I never wanted to sit here in the heart of this foreign country and make myself their judge. That is a role that I was forced to assume, but duty demands that I play this role to the end. [...] With all my might I must remember that I am not dealing with friends here, but rather with enemies (if also defeated ones).67 This dilemma coloured contemporary political analyses of the aftermath of the Nazi regime that denied Germans the very empathy that occupiers from liberal Western democracies felt compelled to acknowledge. Arendt‘s travel report cited at the beginning also vacillated, I think, between shock about the desolate ruins of post-war Germany and the attempt to resist any emotional sympathy for Hitler‘s Germans.

|

||

| _________________________________ | ||

| |

||

|

2 Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (San Diego: Harcourt, 1976), p. 363. 3 Ira Katznelson, Desolation and Enlightenment: Political Knowledge after Total War, Totalitari- anism, and the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003); Dana Villa, ‘Terror and Radical Evil’, in Politics, Philosophy, Terror: Essays on the Thought of Hannah Arendt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), pp. 11-38. 4 W.G. Sebald, ‘Air War and Literature’, in On the Natural History of Destruction, trans. Anthea Bell (New York: Random House, 2003), pp. 1-104, here pp. 9-10. 5 See the critique by Robert G. Moeller, ‘Germans as Victims: Thoughts on Post-Cold War Histories of World War II’s Legacies’, History & Memory, 17 (2005), pp. 147-194; Frank Biess, Homecomings: Returning POWs and the Legacies of Defeat in Postwar Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). 6 Richard Bessel and Dirk Schumann, eds, Life after Death: Approaches to a Cultural and Social History of Europe during the 1940s and 1950s (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Richard Bessel, Germany 1945: From War to Peace (New York: Harper Collins, 2009); Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (New York: Penguin Press, 2005). 7 Reinhart Koselleck, ‘Vom Sinn und Unsinn der Geschichte’, Merkur 51 (1997), 319-334, 324. See also Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, ‘Koselleck, Arendt, and the Anthropology of Historical Experiences’, History and Theory, 49 (2010), pp. 212-236. 8

Cf. Michael Werner and

Bénédicte Zimmermann, ‘Penser

l’histoire croisée. Entre empirie et réflexivité’, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 58 (2003), pp. 7-36; Nicolas Beaupré et al., ‘Pour une histoire

croisée des expériences

d’occupation européennes (1914-1949)’, Histoire

& Sociétés. Revue

européenne

d’histoire sociale, 17 (2006), pp. 6-7; similarly

the account of Nicholas

Stargardt, Witnesses of War: Children’s Lives under

the Nazis (London: Cape,

2005), p. 17. Saul Friedländer argues for an integrated history of the Holocaust that follows a similar trajectory and assumes two perspectives – one

‘from below’ of the Jewish victims

(primarily through diaries) and one ‘from

above’ based on National Socialist policy and administration

(and the

corresponding documents).

Saul

Friedländer, Den Holocaust

beschreiben.

Auf dem Weg zu einer integrierten Geschichte (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2007);

Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the

Jews, 2 vols

(London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1997).

9 The popularity of diaries during the Second World War was noted very early on by Michèle Leleu, Les journaux intimes (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1952). 10 Annette Wieviorka, The Era of the Witness, trans. Jarek Stark (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006). 12 Jochen Hellbeck, Revolution on My Mind: Writing a Diary under Stalin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006); Irina Paperno, Stories of the Soviet Experience: Memoirs, Diaries, Dreams (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009). For an eloquent reading of autobiographical writings from Nazi Germany, see Peter Fritzsche, Life and Death in the Third Reich (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008). 13 Merridale, Ivan’s War. 16 This is true for other diaries, such as Ursula von Kardoff’s, which became available in a critical edition only in 1992. This edition allows a comparison between the original diary and the version compiled in 1947 as well as the published version of 1962. The following entry from 12 April 1945, for example, was omitted from the 1962 edition: ‘And when the others [the Allies] come with their excessive hatred, their gruesome accusations, one must be silent because it’s true’ (Ursula von Kardoff, Berliner Aufzeichnungen 1942-1945, new ed. by Peter Hartl (Munich: dtv, 1992), p. 306). 135. See also Dieter Pohl and Frank Bajohr, Der Holocaust als offenes Geheimnis. Die Deutschen, die NS-Führung und die Alliierten (Munich: Beck, 2006), pp. 65-76; and, more generally, Rafael A. Zagovec, ‘Gespräche mit der Volksgemeinschaft. Die deutsche Kriegsgesellschaft im Spiegel westalliierter Frontverhöre’, in Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, vol. 9.2, ed. Jörg Echternkamp (Munich: DVA, 2005), pp. 289-381; Peter Longerich, ‘Davon haben wir nichts gewußt!’ Die Deutschen und die Judenverfolgung, 1933-1945 (Munich: Siedler, 2006); Michael Geyer, ‘Endkampf 1918 and 1945. German Nationalism, Annihilation, and Self-Destruction’, in No Man’s Land of Violence: Extreme Wars in the 20th Century, ed. Alf Lüdtke and Bernd Weisbrod (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2006), pp. 37-67; Jeffrey K. Olick, In the House of the Hangman: The Agonies of German Defeat, 1943-1949 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); Norbert Frei, ‘Von deutscher Erfindungskraft oder: Die Kollektivschuldthese in der Nachkriegszeit’, in Frei, 1945 und wir. Das Dritte Reich im Bewußtsein der Deutschen (Munich: Beck, 2005), pp. 145-155. 18 Zagovec, ‘Gespräche mit der Volksgemeinschaft’, p. 381. 20 Reinhart Koselleck, ‘Terror and Dream: Methodological Remarks on the Experience of Time during the Third Reich’, in Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, trans. Keith Tribe (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), pp. 205-221; as well as Irina Paperno, ‘Dreams of Terror: Dreams from Stalinist Russia as a Historical Source’, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 4 (2006), pp. 793-824; Paperno, Stories of the Soviet Experience. 21

Archiv zur Geschichte von Tempelhof und

Schöneberg, Sabine

K. (b. 1926), Tagebuch,

Berlin-Schöneberg, 1.9.1944-21.5.1945.

22 Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt, Ingrid H. (b. 1929), Tagebuch, Berlin-Johannisthal, 21.4.-23.5.1945. 23 Kempowski Archiv, Nr 3697: Hertha von Gebhardt (b. 1896), Tagebuch, Berlin-Wilmersdorf, 20.4.-31.7.1945, entry from 28 April 1945. This confrontation with German complicity in Nazi crimes continued after the end of war in the daily interactions between Allies and Germans. See, for example, the diary entry of a nurse on 28 May 1945: ‘The commandant has found a new flame, beneficial to me. In a suitable moment, however, I can converse well with him. He has always been friendly and amiable, to my children as well. Recently he came into my room, picked up little Cornel, gazed at Dagmar and Mathias and said, “Pretty children! – I also have wife and child, one year! The Germans killed both, so!” And he imitated the cutting open of a stomach!! “SS?” I asked. He nodded. (He was a Jew.) – [...] Reinhardt? The Russians say f ive years forced labour?! I cannot grasp the idea. I listen to music! I could go crazy. My dear Reinhardt!’ Berliner Geschichtswerkstatt, Irmela D. (b. 1916), Tagebuch [in letters to her husband Reinhardt D.], Beelitz-Heilstätten bei Berlin 18.5.45-2.9.45, Abschrift 1946: Tagebuch aus der Russenzeit. 25 Marta Mierendorf diary in ‘Ich fürchte die Menschen mehr als die Bomben’. Aus den Tage- büchern von drei Berliner Frauen 1938-1946, ed. Angela Martin and Claudia Schoppmann (Berlin: Metropol-Verlag, 1996), pp. 101-148. On the psychological impact of war and occupation, see Svenja Goltermann, ‘Im Wahn der Gewalt: Massentod, Opferdiskurs und Psychiatrie 1945-1956’, in Nachkrieg in Deutschland, ed. Klaus Naumann (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2001), pp. 343-363; Greg Eghigian, ‘Der Kalte Krieg im Kopf: Ein Fall von Schizophrenie und die Geschichte des Selbst in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone’, Historische Anthropologie, 11 (2003), pp. 101-122. 26 Akademie der Künste zu Berlin, Nachlaß Eva Richter-Fritzsche (b. 1908), Tagebücher 1941- 1945, Berlin-Pankow, 4 May 1945. 27 Ernst Jünger, Jahre der Okkupation (f irst published in 1958), in Jünger, Strahlungen II (Munich: dtv, 1988), 413. The diary entry for 16 May reads: ‘It is in the nature of things that we are more affected by misfortune in our own family, the suffering of our own brother – just as we are more closely caught up in his guilt. They are ours. We must stand for them, must pay for them’ (ibid, p. 451). 28 Atina Grossmann, Jews, Germans, and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), p. 55. 29 This has been overlooked in the otherwise pioneering study by Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery, trans. Jefferson Chase (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2003). See, however, the similar argumentation for Japan after 1945 in John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999). 32 Akademie der Künste zu Berlin, Konrad Wolf Archiv, Nr 2031, Tagebücher [in Russian] 1944/45; see also Konrad Wolf (Archiv-Blätter 14) (Berlin: Archiv der Akademie der Künste, 2005), pp. 84-85. 34 Russian State Archive for Literature and Art (RGALI), Moscow, Fond 2581, op.1, d.1, ll. 118-141: Lazar Bernštein, Zapisnye knižki s dnevnikovymi zapisjami, 1933-1960; Dnevnikovye zapiski o poezdke v Germaniju, 6 March-25 April 1945 before the Oder [River], 7 March 1945. 35 See Lisa A. Kirschenbaum, ‘“Our City, Our Hearts, Our Families”: Local Loyalties and Private Life in Soviet World War II Propaganda’, Slavic Review, 59 (2000), pp. 825-847. 36 Scherstjanoi, Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland, p. 170. 37 Ibid., p. 178. 40 Norbert Frei, ‘“Wir waren blind, ungläubig und langsam”. Buchenwald, Dachau und die amerikanischen Medien im Frühjahr 1945’, Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 35 (1987), pp. 385-401; Dagmar Barnouw, Ansichten von Deutschland (1945). Krieg und Gewalt in der zeitgenös- sischen Fotografie (Basel: Stroemfeld, 1997); Cornelia Brink, Ikonen der Vernichtung. Öffentlicher Gebrauch von Fotografien aus nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslagern nach 1945 (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1998). 41 Imperial War Museum, London, Department of Documents, no. 88/8/1: Lieutenant Colonel M. E. Hancock MC, Berlin Diary, 1945. 42 Ibid. 44 Leonard O. Mosley, Report from Germany (London: Gollancz, 1945), p. 28. 45 George Orwell, ‘Now Germany Faces Hunger’, Manchester Evening News, 4 May 1945, in The Complete Works of George Orwell, vol. 17: I Belong to the Left: 1945 (London: Secker & Warburg, 1998), p. 133. 46 Edgar Morin, L’an zéro de l’Allemagne (Paris: Édition de la Cité Universelle, 1946). 47 In light of expectations of a popular insurrection stoked by Nazi propaganda, the Allied vic- tors did not hesitate during the f irst months of the occupation to issue draconian punishments, including death sentences against German youths, even when their crimes had no recognizable 48 Significantly there is no historical study on consensual relationships between Red Army soldiers and German women. The pioneering account of the Soviet occupation by Norman Naimark, The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949 (Cam- bridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1995), covers only the violence at the end of war. See, in contrast, the extensive literature on GIs and Fräuleins, most recently Heide Fehrenbach, Race after Hitler: Black Occupation Children in Postwar Germany and America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005). 49 Vladimir Gelfand, Deutschland Tagebuch 1945-1946. Aufzeichnungen eines Rotarmisten, ed. Elke Scherstjanoi (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2005), p. 116. For a transcript of the Russian original, see http://www.gelfand.de. Many Soviet deserters originally stationed in Germany made similar statements in interviews conducted by American social scientists during the early 1950s. See the extensive transcripts of the Harvard Émigré Interview Projects (for example, vol. 28, no. 541), Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. 50 Gelfand, Deutschland Tagebuch, p. 205. 52 Imperial War Museum London, Department of Documents, Lieutenant Colonel R.L.H. Nunn, Memoirs, written in 1946, p. 172. 53 Peregrine [i.e. Isaac Deutscher], ‘European Notebook: “Heil Hitler!” Password for a Flat in Germany’, The Observer, 9 December 1945. For this shift in British public opinion see also Mark Connelly, ‘The British People, the Press, and the Strategic Campaign Against Germany’, Contemporary British History, 16 (2002), pp. 39-58, similarly for the United States: Astrid Eckert, Feindbilder im Wandel. Ein Vergleich des Deutschland- und des Japanbildes in den USA 1945 und 1946 (Münster: Lit, 1999). 55 Stephen Spender, European Witness (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1947), p. 235. 56 John Dos Passos, Tour of Duty (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1946), p. 319. 58 Stig Dagerman, German Autumn, trans. Robin Fulton (London: Quartet Encounters, 1988), pp. 9-10 and 12-13. 60 The critique of Allied occupation within the German public beginning in 1947 has been analysed by Josef Foschepoth, ‘German Reaction to Defeat and Occupation’, in West Germany under Construction: Politics, Society, and Culture in the Adenauer Era, ed. Robert G. Moeller (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). Foschepoth does not interpret this critique as a result of Allied occupation policies, but merely as a German strategy to reject notions of collective guilt. 61 For example, Eric Hobsbawm tells of such a disillusionment (which, however, was soon eclipsed by the Cold War). The British communist and historian came to Germany in 1947 as a re-education officer and was impressed by the stories of one of the participants in his seminars – Reinhart Koselleck – about his experience as a German POW in a Soviet camp. Eric J. Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth-Century Life (New York: Abacus, 2002), pp. 179-180. 62 See, for example, Riccarda Torriani, ‘“Des Bédouins particulièrement intelligents?” La pensée coloniale et les occupations française et britannique de l’Allemagne (1945-1949)’, Histoire & Sociétés. Révue européenne d’histoire sociale, 17 (2006), pp. 56-66. 63 Similarly, Klaus Dietmar Henke, ‘Kriegsende West – Kriegsende Ost. Zur politischen Auswirkung kollektiver Schlüsselerfahrungen 1944/45’, in Erobert oder befreit? Deutschland im 64 E. Berg, ‘Dva goda v okkupirovannoi Germanii’, Pamjat’. Istoričeski Sbornik, 5 (1981/82), pp. 7-41, 10 and 12. 65 Mark Edele, Soviet Veterans of the Second World War: A Popular Movement in an Authoritarian Society, 1941-1991 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). – Winning the Memory Battle: The Legacy of Nazism, World War II, and the Holocaust in the Federal Republic of Germany’, in The Politics of Memory in Postwar Europe, ed. Claudio Fogu et al. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), pp. 102-146; Aleida Assmann, Der lange Schatten der Vergangenheit. Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik (Munich: Beck, 2006). 67 Peter Weiss, Die Besiegten (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1985; Swedish original, 1947), p. 57. See also: Wilhelm Voßkamp, ‘“Ein unwahrscheinlicher Alptraum bei hellem Licht”. Peter Weiß’ Berliner Phantasmagorien “Die Besiegten”‘, German Politics and Society, 23 (2005), pp. 128-137. |

| Когда закончилась Вторая мировая война, Европа лежала в руинах. Однако в политическом и социальном плане годы между 1943 и 1947 были временем драматических реконфигураций, которые оказались основополагающими для формирования сегодняшней Европы. Этот том посвящён важнейшему периоду от начала конца нацистского правления до начала холодной войны. В нём показано, как повседневный опыт европейцев в течение этих пяти лет определил переход их обществ от войны к миру. Эссе исследуют эти изменения в различных масштабах и на различных уровнях с целью углубления нашего понимания того, как заканчиваются войны. | ||

Опубликовано Amsterdam University Press в 2015 году Из книги «В поисках мира после войны: Европа, 1943–1947» Стефан-Людвиг Хоффман |

||

| В

поисках мира после войны: Европа, 1943-1947 гг. |

||

| |

||

|

I

Вернувшись в Нью-Йорк весной 1950 года после нескольких месяцев путешествия по послевоенной Германии, Ханна Арендт с неподражаемой проницательностью описала любопытный контраст между ужасающими разрушениями немецких городов и очевидным безразличием их жителей. Такое сопоставление, признала она, можно найти и в других странах Европы. Но нигде этот кошмар разрушений и ужасов не ощущается и не обсуждается в меньшей степени, чем в самой Германии. Отсутствие реакции заметно повсюду, и трудно сказать, означает ли это полусознательный отказ поддаться горю или подлинную неспособность чувствовать. [...] Это общее отсутствие эмоций, во всяком случае, это явное бессердечие, иногда прикрытое дешевой сентиментальностью, является лишь наиболее заметным внешним симптомом глубоко укоренившегося, упрямого, а порой и злобного отказа посмотреть правде в глаза и примириться с тем, что действительно произошло¹. Арендт уже касалась этого противоречия между масштабами насилия во время войны и последующим безмолвием немцев в своей книге о тоталитаризме, которую она начала писать в 1945 году и закончила сразу после посещения послевоенной Германии². По мнению Арендт, национал-социализм был совершенно новой формой правления, которая не только ограничивала свободу и совершала чудовищные преступления. Террор, идеология и постоянное чрезвычайное положение, утверждала она, создали мир опыта, который никогда прежде не служил основой для политики: «Третий рейх» за пределами реальности и вымысла, который нашёл свой номос в концентрационных лагерях и приостановил там даже различие между жизнью и смертью. Не только для Арендт эта новая, тотальная форма власти в 1930-х и 1940-х годах представляла собой радикальный разрыв с прошлым, который не мог быть осмыслен с помощью традиционных политических, правовых и моральных концепций³. Геноцидная война и колониальное порабощение Восточной Европы предстали как реализация нацистской идеи переопределения политики, «биополитики». В отличие от этого, в «Истоках тоталитаризма» есть всего несколько абзацев, которые непосредственно касаются вопроса о том, как гитлеровские немцы вышли из этого эмпирического мира в момент полного поражения. Когда террор закончился, утверждала Арендт, закончилась и вера в те догмы, за которые ещё недавно члены нацистской партии были готовы пожертвовать жизнью. Она подтвердила внезапность этого поворота, который многие современные наблюдатели (а позднее и историки) сочли столь неправдоподобным и морально неприятным. Только во время своей поездки по послевоенной Германии Арендт, как она считает, осознала «последствия нацистского правления», как разрыв, так и преемственность. Арендт не считала немцев, с которыми она столкнулась в 1949 году, нацистами. Тем не менее, она считала, что в результате пережитого мира Третьего рейха у них отсутствовала любая форма человеческого сочувствия, будь то к собственным погибшим, страданиям беженцев, виду разрушенных городов или судьбе убитых евреев. Спустя более шестидесяти лет после окончания войны вопрос, поставленный Арендт об эмоциональном потрясении, сопровождавшем переход от тотальной войны к холодному миру, остаётся в центре историко-политических дебатов в Германии после холодной войны. В своём эссе «Война в воздухе и литература» В.Г. Себальд переформулировал этот вопрос в широко обсуждаемое утверждение о том, что масштабы разрушений в немецких городах почти не оставили «следов боли» в немецкой коллективной памяти. Согласно Себальду, после 1945 года немцы жили так, словно ужас войны прошёл мимо них как кошмарный сон, не оплакивая ни погибших, ни разрушения своих городов. Они не только молчали после войны о своём участии в преступлениях нацистского режима, утверждал Себальд, но и так и не смогли выразить словами экстремальные коллективные переживания последнего года войны⁴. Тезис Себальда послужил непреднамеренным толчком для волны реколлекции в немецких СМИ, которые — после «примирения» с преступлениями, совершенными в Европе вермахтом и нацистскими Sondereinheiten — теперь хотели говорить о страданиях гражданского населения Германии в конце войны. Романы, художественные и телевизионные документальные фильмы о конце нацистского правления, воздушной войне союзников и насилии, сопровождавшем продвижение Красной армии, были представлены в этом контексте как нарушение табу. Однако, вопреки утверждению Себальда, немецкие гражданские жертвы войны никогда не были «своего рода табу, как постыдная семейная тайна», ни для поколения, пережившего войну на собственном опыте, ни для тех, кто, подобно Себальду, вырос в тени нацистского насилия. Скорее, воспоминания немецких гражданских жертв войны были идеологически искажены и разделены. Самое позднее, начиная с 1947 или 1948 года, «англо-американо-империалистическая» воздушная война стала пропагандистской темой в Восточной Германии, в то время как, наоборот, страдания немцев под тиранией советской власти — судьба военнопленных, в частности, и немцев в «зоне», в целом — стали цементом, скрепляющим антикоммунизм на Западе⁵. Таким образом, если этот «след боли» вообще исчез, то только в официальном сознании на Востоке и Западе в 1970-е и 1980-е годы, параллельно с окончательным исчезновением руин. Тем не менее, 1940-е годы — период между конференцией в Ваннзее и Всеобщей декларацией прав человека — представляют собой нечто вроде переломного момента в истории двадцатого века, который до сих пор мало изучен. За падением в войну и геноцидом последовало возвращение к мирному и, по сравнению с довоенной Европой, принципиально новому политическому порядку. «Катастрофический национализм» немцев втянул Европу в немыслимый и, казалось, бездонный водоворот насилия, причём наибольшее число погибших за всю войну пришлось на 1944–1945 годы, когда поражение Германии было уже очевидным. Это делает ещё более невероятной констелляцию 1947 и 1948 годов, когда вчерашние враги стали стратегическими партнёрами нового глобального конфликта, в тени которого смогли возникнуть демократии, по крайней мере, в постфашистских обществах Западной Европы и в Японии⁶. Между этими двумя крайностями лежит переломный момент окончания войны, понимаемый здесь как пятилетний промежуточный период, который начался в 1943 году с надвигающегося поражения Германии в Восточной Европе и завершился только в 1947 году с началом холодной войны. Несколько лет между катастрофическим поражением и началом оккупационного правления представляли собой драматическую фазу потрясений не только для немецкого общества. Хотя политическая перестройка мира и Германии в 1945 году хорошо изучена, меньше внимания уделяется вопросам восприятия этих эпохальных потрясений: как война, геноцид, разрушение и оккупация вошли в язык современников? Как победители и побеждённые выходили из экзистенциальной вражды войны? Где видны эмоциональные следы насилия? Другими словами, современные историки только начали заниматься вопросом, поднятым Ханной Арендт и В.Г. Себальдом, о субъективном восприятии участников этого эпохального разрыва. Даже современные свидетели, когда их сегодня спрашивают об этом пережитом мире, говорят о нём как о чужой и нереальной ничейной земле. Таким образом, следующие размышления начинаются с гипотезы о том, что история этого переломного момента 1940-х годов должна начинаться с анализа тех частных текстов — особенно дневников, — в которых современники фиксировали своё восприятие происходящих событий. В момент эпохального разрыва прежние ожидания рушатся, и возникают новые реалии, которые следуют другим правилам того, что может быть выражено. Как отметил Райнхарт Козеллек, «сама история всегда происходит только в среде восприятия участников». Представления акторов о том, что они делают и чего они не должны делать, являются элементами, из которых, перспективно фрагментированных, складывается история. Представления и волеобразование, желания, порожденные лингвистически и прелингвистически, восприятие чего-то как истинного и придание этому истинности — всё это включается в ситуацию, из которой кристаллизуются события. То, что различные агенты считают реальным в истории по мере её возникновения и, таким образом, осуществляют в действии, плюралистически составляет грядущую историю⁷. Это также означает, что катастрофический опыт разрыва и потрясений 1940-х годов не может быть понят исключительно с одной точки зрения — и это, опираясь на Козеллека, является моей второй гипотезой. Принципиально разные перспективы побеждённых, оккупантов и освобождённых составляют разрывной опыт геноцидной войны, оккупации и послевоенной реконфигурации. История истории этих связанных между собой асимметричных восприятий и взаимодействий, сопровождавшихся насилием, в период после 1945 года должна стремиться осмыслить события, исходя из лингвистически осажденного эмпирического мира участвующих субъектов, которые, в свою очередь, всегда были также наблюдателями⁸. Таким образом, задача транснациональной истории 1940-х годов также состоит в том, чтобы соотнести несовместимый или асимметричный опыт насилия и потерь, а также их перспективность, не смешивая и не гармонизируя их в ретроспективе.II