Vladimir Gelfand – memoirist, participant of World War II. Known as the author of published diaries about the years of service in the Red Army (1941–1946), repeatedly published in Russian and translated into German and Swedish. This is the first and only personal diary of a Red Army officer, which is available in German.

You can read a detailed biography about Vladimir, his family, and military service during the Great Patriotic War in the "Biography" section.

Diaries and letters

The diary of Vladimir Gelfand can be read at the links below:

Text version

Scans from the original

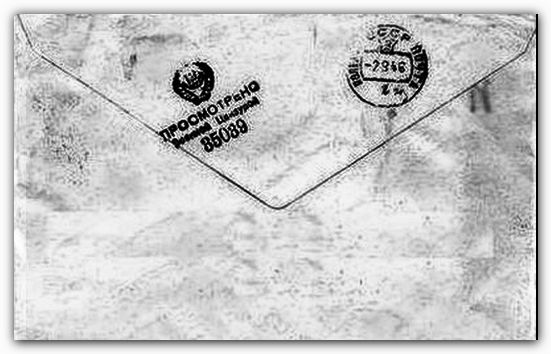

Letters from Vladimir Gelfand can be read at the links below:

Text version

Scans from the original

Biography

Childhood and youth

About family

1923 - 1926Vladimir Gelfand was born on March 1, 1923 in the village of Novoarkhangelsk, Kirovograd Region Ukraine. He was the only child in a poor Jewish family. Vladimir’s mother, Nadezhda Vladimirovna Gorodynskaya (1902-1982), was from a low-income family with eight children. In her youth, she earned money by giving private lessons. In 1917, she joined the RSDLP(b) and, as Vladimir mentioned in his biography, took part in the Civil War. In the 1920s, she was expelled from the party with the wording “for passivity”. This interfered with her career, but saved her from subsequent repressions. Father, Nathan Solomonovich Gelfand (1894-1974), worked at a cement plant in Dneprodzerzhinsk. Unlike his wife, he remained non-partisan.

Relocation

1926 - 1933In 1926, in search of a livelihood, the young family moved to the Caucasus. Vladimir and his parents settled in Essentuki, where his father’s parents lived, but already in 1928 returned to Ukraine in the city of Dneprodzerzhinsk, Dnipropetrovsk region. Here, his father worked as a foreman at a metallurgical plant and, according to Vladimir's diaries, was a "drummer". Mother was a teacher in a factory kindergarten, which Vladimir, among other children, went to. In 1932, she changed jobs, moving to the personnel department of a large metallurgical enterprise. In 1933, the family moved to Dnepropetrovsk.

Parents. Education

1933 - 1941Vladimir's parents broke up when he was in school. Nevertheless, he studied successfully. During his school years he took an active part in public life: he was an editor of the wall newspaper, an organizer of art recitation contests, an agitator-propagandist, and joined the Komsomol. After high school, Vladimir entered the Dnepropetrovsk Industrial Workers' Faculty (now the National Metallurgical Academy of Ukraine), having managed to study there three courses before the war.

The Great Patriotic War

Years of war

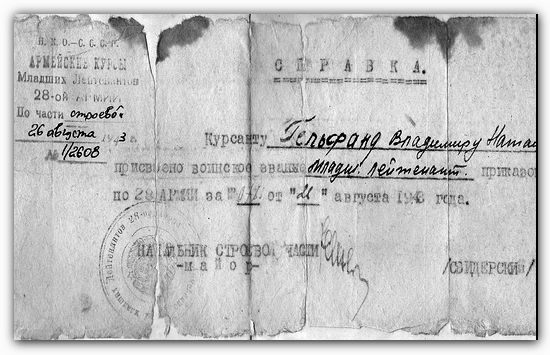

1941 - 1945The German attack on the Soviet Union interrupted the formation of Gelfand. When enterprises, public institutions and a significant part of the city’s population were evacuated in August 1941, Vladimir moved to Essentuki, where he settled with his aunt, his father’s sister. In Essentuki, Vladimir worked as an electrician and had reservation armor. Nevertheless, in April 1942 he turned to the draft board and on May 6 became a member of the Red Army. He was trained at an artillery school near Maykop in the western Caucasus and received the military rank of sergeant.

In July 1942, when the Caucasian oil fields became the direct target of the German offensive, Vladimir Gelfand was on the southern flank of the Kharkov Front (as he writes in his Diary, entry dated 06.16.1942) as commander of the mortar squad.After the war

1946 - 1983At the end of 1946 Vladimir Gelfand was demobilized. In September 1947, he began his studies at the Faculty of History and Philology of Dnepropetrovsk State University. Since August 1952, Vladimir worked as a teacher of history, the Russian language and literature at the Zheleznodorozhniki College No. 2 in Molotov (Perm). In February 1949, he married Berta Davidovna Koifman, a girl whom he had known since studying at school and had been in correspondence with her throughout the war. Soon the marriage with Berta was in crisis. In 1955, Vladimir left his wife and son and returned to Dnepropetrovsk, where he joined the college as a teacher. In 1957, Vladimir Gelfand met with a graduate of the Institute of Pedagogical Education of Makhachkala Bella Efimovna Shulman

. In August 1958, Vladimir divorced his first wife and soon married Bella. Living conditions remained difficult. For more than 10 years, the Gelfand family of four has rented a private living space of 10 m². Only in the late sixties did the family of the war veteran receive a state apartment. Vladimir Gelfand had health problems. In 1974, his father died, in 1982 - his mother. Vladimir survived her only for a year.

You can read the full text here:

About the writer diary

"The diary is unique for several reasons. Firstly, in terms of chronological scope and volume of entries: it begins with the last pre-war months of 1941, ends with the return from Germany, where the author served in the occupation forces, in the fall of 1946. Actually, Vladimir Gelfand also after the war he continued to keep a diary, but he kept it not so systematically, and the events described in it were more interesting for the history of everyday life of Soviet people in the second half of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1980s, which is a completely different story. I immediately noticed that diaries of equally wide temporal coverage still occur, albeit infrequently. I will mention the diaries of Nikolai Inozemtsev and Boris Suris, of the unpublished ones - the diary of Vasily Tsymbal. However, Nikolai Inozemtsev served in high-powered artillery, which was used mainly during offensive operations, located far enough from the front line, as a result of which the author spent most of the war in the rear, in anticipation of the offensive. Boris Suris was a military translator at the headquarters of the division and was rarely at the forefront by service. Gelfand - and this is the second feature that allows him to consider his diary unique - was a mortar man, during the period of hostilities he was practically at the very front end; there was only infantry ahead. Serving in high-power artillery assumed a certain educational level, not to mention staff work; therefore, the environment of Gelfand is significantly different from the environment of Inozemtsev or Suris. This is the most “ordinary people”; among Gelfand's colleagues there are a lot of very illiterate, and even simply illiterate, for whom he sometimes writes letters. Thirdly, and this is perhaps the most important: the diary is unprecedented in frankness. When reading diaries, one can often notice a certain internal limiter: their authors seem to assume an outside reader, sometimes they consciously write with this “external” reader in mind. Gelfand's case is fundamentally different: at times the text of the diary is hard to read: the author describes his own humiliation, sometimes - unseemly acts. With unparalleled frankness, he writes about his sexual problems and “victories,” down to physiological details.

The diary is also unique in one more respect: this is perhaps the only text currently known that describes in detail the "labors and days" of a Red Army officer in occupied Germany in 1945–1946, his relationship with the Germans (especially with the Germans), - describing without any omissions and glances.

The author of the diary undoubtedly belongs to the category of graphomaniacs. He can’t write, he writes constantly, under any conditions. He writes letters to relatives and friends (mainly school ones; however, if he accidentally met a girl somewhere, then she also falls into the list of his correspondents), writes poems, and articles in newspapers (real and wall). He writes letters for colleagues who are at odds with a letter or who want to be written “beautifully”:

“For several days in a row I write letters to other persons. Here, Pyotr Sokolov, our company commander, wrote two letters for his girlfriend Nina. Then Kalinin asked his little daughter to answer, who asks to send an article to the local wall newspaper, but he does not know how best to answer so as not to offend her feelings. Previously, Rudneva wrote the girl. Glantsev’s wife - two letters, Chipak - a letter home, etc. ” (01/15/1944).

But the main thing is that Gelfand keeps a diary, which he calls his “friend” (11/07/1941). More than a year later, he writes, referring to the diary:

"Diary, pal dear! And today I was drinking tea from the roots! Sweet as with sugar! Sorry, I did not leave you! But it doesn’t matter - you just need to smell the roots - here they are, in my hands, so that you are convinced of the veracity of my words. And why do you need sweets other than mine, because you experience everything along with me - the same joys and sorrows » (09/03/1942).

Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor, Director of the International Center for the History and Sociology of World War II and its Consequences HSE Oleg Budnitsky

the diary will open in a new window. At the bottom of the menu and paging arrows

(english)

Excerpts from the diary(the link version is only in russian)

Diary 1941 Diary 1942 Diary 1943Diary 1944 Diary 1945 Diary 1946

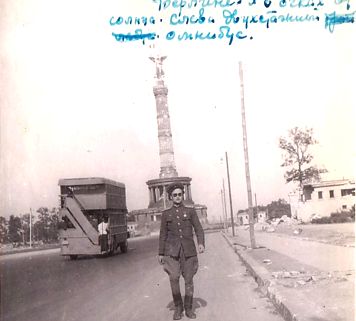

Photos by Vladimir Gelfand

01/14/1946

[...] He arrived in Potsdam late — at 8 pm — he delayed the auction: he bought a camera, a watch, two pens, a cap — half of what he had planned. He went around the photo studio and was with the artist. He took pictures and left his photos for enlargement.

[...] The camera of the German brand "Akfa". Square, black in the form of a celluloid. Rare in appearance. The lens is not visible from above - it is inside. The aperture is weak, about 7 by 7. In one place, the edge is broken and roughly grabbed with glue at the junction of the two halves of the device - it consists of two parts. The latches from two parts are white - the color of steel. They are written in German "tsu, auf."

The device rests on one latch - the other is broken. There are two steel bushings for primitive shutter speed and instant shooting, a light filter, two viewfinders for longitudinal and transverse shots. A window with red glass through which you can monitor the movement of film frames, without cover - it is broken.

The device works with 6x9 film on a wooden reel. The internal structure of the device is very simple, although the external appearance inspires involuntary respect for its unusualness.

04/21/1946

[...] Happened in a German exchange store. I gave the camera for harmonica. When I already wanted to leave, - an old man with a beard and glasses came up to me and in Russian asked if I had one more - my daughter wanted to exchange for an accordion. I was delighted - the guys (officers) asked me to get an accordion, and I had two cameras.

05/22/1946

[...] Today I sold cigarettes and food to a tailor. There are a lot of films now. There is a fixer and developer. My device’s shots are not bad, it remains only to learn to manifest and fix, and for this we need suitable conditions: a dark room and a photographer - a teacher. Velten has the opportunity to take photos seriously.

[...] Yesterday I took pictures of drivers. He deliberately chose historical places, and it was important for me not to capture these grimy fortunes in the pictures, but how much Berlin was, in all its emptiness and grandeur.

06/23/1946

[...] Now a new idea has ripened - a camera of the “Leiki” type of 6 thousand, and a Liliputik radio receiver of five lamps and 4 thousand brands. Both things must be acquired by any means.

08/27/1946

[...] Managed to ride a bike on the "Akfa" and get there ten films, developer and fixer. Now they promise to transfer us to Rummelsburg, and there again the parking, apparently long and joyless. Hurry, Berlin, let us out of your tenacious, wide embrace. Or do you want to compete in your affection with little German Ruth, who tormented her with her wills, confessions, prayers, reproaches and her naivety?

09/24/1954

[...] When he returned, a surprise awaited me at home: a summons to appear to the investigator. For what reason? I am a little worried: whether this is due to the loss of my things, or for old sins - with a camera five years ago? I don’t feel anything else for myself. What if I’m not coming back from there? Scary alarming time now.

05/11/1965

[...] - There is evidence. One girl from group 14 herself boasted that you photographed her naked on the beach and showed a photo card.

- I didn’t go myself, but with the craftswoman, with the whole group, we went to the beach and took pictures of the whole group.

But Borodavkin intimidated me:

- You retire with them and photograph naked, and then take 40 kopecks per card.

I replied that I took pictures for free, that I didn’t retire, that it was a cult trip, and that Borodavkin was “naked” himself.

Go to

Bibliography and media materials

Publications

- 2002 "bbb battert" Baden-Baden, Germany, "Tagebuch 1941—1946"

- 2005 "Aufbau" Berlin, Germany: "Deutschland Tagebuch 1945-1946"

- 2006 "Ersatz" Stockholm, Sweden: "Tysk dagbok 1945-46"

- 2008 "Aufbau-Tb" Berlin, Germany: "Deutschland Tagebuch 1945-1946"

- 2012 "Ersatz" [E-book] Stockholm, Sweden: "Tysk dagbok 1945-46"

- 2015 "Росспэн", "Книжники" Moscow, Russia: "Дневник 1941–1946"

- 2016 "Росспэн", "Книжники" Moscow, Russia: "Дневник 1941–1946"

Bibliography

A large number of excerpts from the diaries of Vladimir Gelfand, his photographs from occupied Germany, case studies of diaries are contained in books:

go toCombat Journal 301 Rifle Divisions in the Battle of Berlin

301st Stalin Order of the Suvorov 2nd degree infantry division ... Date of birth - August 1943. Place of birth - Kuban, Slavic district, Anastasievskaya village. Rifle regiments: 1050, 1052, 1054. Formed on the basis of two rifle brigades - the 34th and 157th, which came to the Kuban from the foothills of the Caucasus after the defeat of the Nazi troops. It took the sailors from the 34th separate and 157th rifle brigades about four months to overcome the distance from North Ossetia to the Kuban with battles. On this way hundreds of settlements of North Ossetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Stavropol, Kuban were liberated. The division included independent units and subdivisions: the 823rd artillery regiment, the 337th separate fighter anti-tank division, the 757th separate communications battalion, the 592nd separate engineer-combat battalion, the 341st medical sanitary battalion, field mail, the division field bakery and other units. Colonel Vadimir Semenovich Antonov was appointed the division commander, lieutenant colonel Alexander Semenovich Koshkin, deputy political director and political department chief, and lieutenant colonel Mikhail Ivanovich Safonov, chief of staff. The commanders of the regiments, battalions, companies and other combat units were the commanders of the 34th and 157th rifle brigades. In the compound, there were up to 12 thousand soldiers and officers. The personnel was equipped with battle sailors, cavalrymen, who became famous in the battles near Mozdok and Ordzhonikidze, and with a new replenishment of the Kuban Cossacks. Two hundred girls and two thousand men, mainly from the villages of Slavyanskaya, Anastasievskaya and the hamlets of the Slavyanskiy district, came under the combat banners of the regiments and divisions of the 301 rifle division.

You can read the Combat journal here.:

(the link version is only in russian)

Scans from the originalText version

Press Publications

The section contains media materials about the diaries of Vladimir Gelfand. Publications in Germany, Denmark, Ukraine, Israel, England, Sweden, Russia, Ireland, USA, Canada, Greece, Italy, Austria, Spain, France, Czech Republic, Brazil, Croatia, China, Republic of Korea, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, Panama, Peru, Paraguay, Vietnam, Indonesia, Azerbaijan, Republic of Belarus, Netherlands, Chile, Mexico, Romania, Turkey, Estonia, Latvia, Slovakia, Poland, Uzbekistan, Finland, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, India, Egypt, Portugal, Albania, Belgium, Argentina, Singapore. When you go to the media page, there are lines with the names of the publication. Each line is a link to the publication page.

"Diary of a Soviet soldier. Its strength in describing reality, which has been denied for a long time and has never been described in the perspective of everyday life. Despite all the horrors, this is an exciting read that came to us after many years. It is more than joyful that these records, even from 60 years of delay, they became available, at least for the German public, because it was not such a perspective that these records show for the first time the face of the victorious Red Army soldiers, which makes it possible to understand the inner world of Russian soldiers. For Putin and his post-Soviet it will be difficult for the guards to close this diary in a locker with poisons of propaganda hostile to Russia "

Per Landin, Schweden, "Det oändliga kriget", in: Dagens Nyheter

"The German diary 1945-46 Gelfand's is remarkable in many respects. This is an unusual description by an eyewitness of the liberation of Poland and East Germany by the Red Army. Since the Red Army was forbidden to keep a diary, probably for security reasons, readers already have reason to be grateful to Ukrainian lieutenant Vladimir Gelfand who boldly violated this ban, although the diary is insufficient in some respects, it may be a definite counterweight to the army of historical revisionists who work "to turn the great victory of mankind over Hitlerism into a brutal attack by the Stalinist guards on Western civilization"

Stefan Lindgren, Schweden, "Dagbok kastar tvivel över våldtäktsmyten", in: Flamman

"This is very private, uncensored evidence of the feelings and moods of the Red Army and the occupier in Germany. For all that, it is indicative that the young Red Army saw the end of the war and the collapse of German society. We get completely new views on the military community of the Red Army and its moral state, which too often was glorified in Soviet images.In addition, Gelfand's diaries oppose common theses and the military successes of the Red Army should be attributed mainly to the system of repressions. one can see about Gelfand’s personal experiences that there were also caring relationships between the victorious and the vanquished women in 1945/46. The reader gets a reliable picture that German women also sought contact with Soviet soldiers — and this was not only for material reasons or with the need for protection "

Dr. Elke Scherstjanoi, Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin

“Among many eyewitness accounts of the end of World War II in Germany, a diary of a young Red Army lieutenant appeared, who participated in the capture of Berlin and remained in the city until September 1946. The German diary of Vladimir Gelfand was the subject of widespread media interest, which throws comments in a new way light on a review of existing German tales of the fall of Berlin and the attitude of the Soviet invaders to the German population at that time "

Anne Boden, Trinity College Dublin, Bradford Conference on Contemporary German Literature

"Gelfand's diary reflects the sentiments of Soviet troops at the final stage of World War II and after it. A Jew of Ukrainian descent finds himself in Germany with great spontaneity and a growing thirst for revenge, which coiled among the troops participating in Operation Wisla-Oder. Hatred for the enemy all more and more identified with the entire German people. Gelfand witnesses destruction, looting, deaths and betrayals. Several cases of violence and rape of German women are recorded in diaries. I'm a sensitive observer and a partner in one person and not trying to hide acts of revenge and looting. Gelfand Blogs are a unique chronicle of the Soviet occupation of Germany"

Università Ca' Foscari, Venezia "Stupri sovietici in Germania (1944-45)", Matteo Ermacora e Serena Tiepolato

go to